Hugo, enemy of the State.

Chronology of an escape.

VICTOR HUGO LETTER TO JOSÉPHINE TRÉBUCHET, DECEMBER 19th, 1851

After the coup d’état of December 2, 1851, Victor Hugo goes into hiding. At the head of the resistance committee comprising members of the left and the extreme left, he tried to convince the people for rebellion, but quickly understood that he would not succeed. After the massacre of the main boulevards (December 4), his head is priced, he must organize his escape.

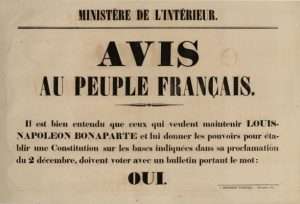

Ministère de l’Intérieur. Avis au peuple français, (Imprimerie nationale, plébiscite décembre 1851) © BnF

Juliette Drouet, who watches over him, receives a visit from a former friend, Mrs. Lanvin, who offers to make the passport of her husband, a typographer, available to Victor Hugo. They had to find a destination and a motive for travel. Juliette Drouet had another friend whose husband was a printer in Brussels: he agreed to write the letter of invitation to Brussels for Mr. Lanvin, which was necessary to obtain a passport.

Juliette Drouet lithographiée par Alphonse-Léon Noël, 1832

Victor Hugo was lucky to have his first cousin and old classmate, Adolphe Trebuchet (1801-1865), head of the Health Council at the Paris Police Prefecture since 1848: Trebuchet most likely facilitated the manufacture of the passport which allowed Victor Hugo to pass through Belgium under the identity and clothing of the typographer Jacques-Firmin Lanvin, on the night of December 11 to 12, 1851.

On the morning of 12 December, he arrived in Brussels. Hugo found a room near the Grand Place, in the small hotel of the Green Gate, which disappeared in 1905, rue de la Violette, No. 31. His room on the 2nd floor and bears the number 9: “I lead a religious life. I have a bed as big as a hand. Two straw chairs. A room without fire. My bulk expenditure is 3 francs five pennies a day, all-inclusive“. He will remain there until January 5.

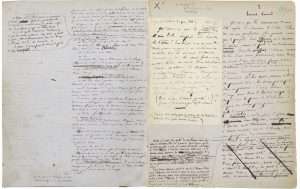

On 14 December, Juliette Drouet joined him in Brussels with his famous “manuscript trunk”, which contained all his past works and some of those to come, starting with two thirds of the future Misérables. She settled in a small room in the Saint-Hubert galleries (passage of the Princes, 10).

Fragment of Les Misérables from the “manuscript trunk”. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Manuscrits, NAF 13380, fol. 294v°, 296-298 © Bibliothèque nationale de France

On 18 and 19 December, Mrs. Victor Hugo, who stayed in Paris to watch over her daughter Adele and her two sons in prison, joined her husband, at her request, to discuss “a host of essential and impossible things to write”. He took the opportunity to entrust her with his mail, knowing that the post office was already closely monitored; including a letter for each of his two faithful friends Paul Meurice and Auguste Vacquerie, a letter for his daughter Adele, and a letter to thank his cousin Josephine Trevover, who regularly heard from her family since the coup:

“Brussels – 19 Xbre

My wife tells me all your lovely gratitude, dear cousin, how to thank you. Alas! I no longer have a long arm, otherwise I would kiss you from Brussels to Paris.

Tell my dear and good cousin that my heart is full of him. I have fought for the right, for the truth, for the righteous, for the people, for France, against crime in all its forms, from treason to atrocity. We have succumbed, but valiantly and proudly, and the future is ours. Praise God always!

I kiss your hands, my cousin.

Victor H.

Kiss my dear daughter for me.”

This family and confident letter (Adolphus was almost a brother to him, despite their differences of opinion), one of the first of the exile, is written in haste, in the whirlwind of decisions to be made. She sums up the situation like the others. Victor Hugo wrote to Auguste Vacquerie the same day: “I have just fought, and I have shown a little what a poet is.” And to Paul Meurice:

“Dear friend, I hope this will be short. If it’s a long time, we’ll smile longer. What a shame! Fortunately the left valiantly held the flag. These wretched have accumulated crimes on crimes, ferocity on treason, cowardice over atrocity. If I am not shot, it is not their fault, nor mine. »

At the same time as he thanked his cousin, Victor Hugo was worried about the real Jacques-Firmin Lanvin, who remained in Paris in the midst of a dictatorship, perhaps compromised by his generosity. His “dear and good cousin” Adolphe Trebuchet, using the expression that Victor Hugo used for his wife (“I no longer have a long arm”), will appease his scruples with a letter dated December 25, the first Christmas of exile:

“Rest assured, only you ran danger, Lanvin did not run any. On the contrary, he is rewarded, and that is right. He did the right thing by lending you his passport. I can give him a place, and I’ll give it to him. And in this place is attached, for the future, a small pension. This brave Lanvin owes this to his good deed, and to you. You see the outlaws have a long arm. I kiss you and I’m devoted to you.

Your cousin,

Adolphe Trebuchet”

Is it to be understood that at least part of the new government, for a rather obvious image question, preferred for the moment to know Victor Hugo living abroad rather than dead (or live) in France? That is a possibility that should not be ruled out.

In any case, it is from 19 December 1851 also that dates what is undoubtedly Victor Hugo’s first reflection on the threshold of exile, and which testifies to the same satisfaction of the duty accomplished:

“Every day the thickness between death and me decreases.

I see the transparency of eternity.”

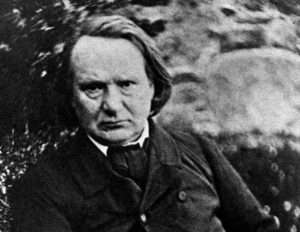

Victor Hugo on exile in 1852 © Getty / Hulton Deutsch / Collection Corbis Historical

In her small room in the passage of the Princes, again on 19 December, between three and four o’clock in the afternoon, Juliette Drouet, who found him preoccupied, sought to comfort him, in a vein hardly less prophetic:

“My Victor, I have the presentiment, this exile, so sadly and so anxiously begun, will end in all the holy joys of the family and in all the splendor of the triumph of your ideas and the glory of your martyrdom. I am sure how I am to worship you until my last breath.”

By Jean-Marc Hovasse, July 2020