APOLLINAIRE, Guillaume (1880-1918)

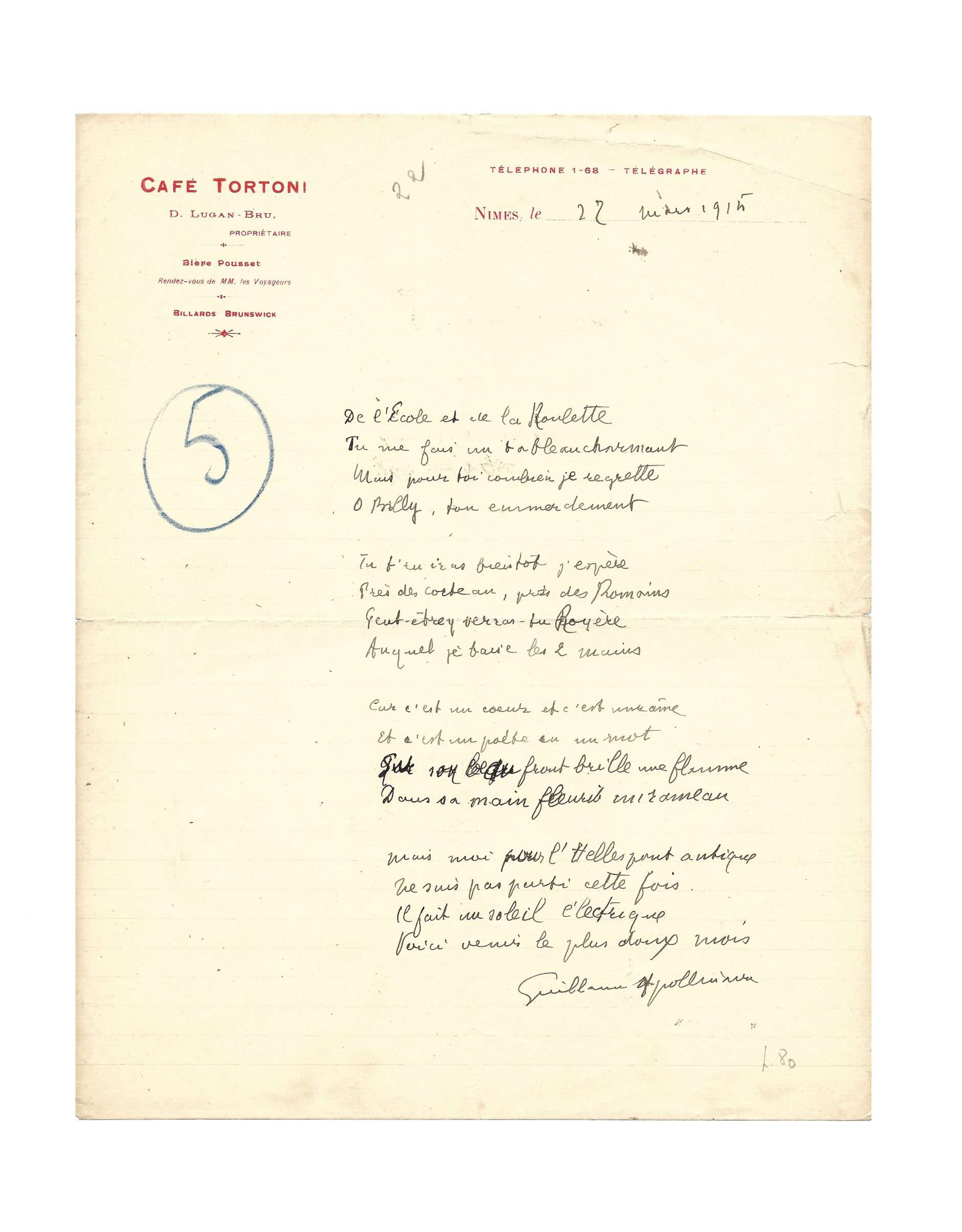

Epistolary autograph poem signed « Guillaume Apollinaire », to André Billy

Nîmes, 20th March 1915, 1 p. in-8° on Café Tortoni’s letterhead

« On his beautiful forehead shines a flame / In his hand blooms a twig »

Fact sheet

APOLLINAIRE, Guillaume (1880-1918)

Epistolary autograph poem signed « Guillaume Apollinaire », to André Billy

Nîmes, 20th March 1915, 1 p. in-8° on Café Tortoni’s letterhead

Some spots, tears on margins, fold mark

Brilliant improvised poetic epistle from the Café Tortoni in Nîmes, where the poet had his habits

« De l’École et de la Roulette

Tu me fais un tableau charmant

Mais pour toi combien je regrette

O Billy ton emmerdement

Tu t’en iras bientôt j’espère

Près des Cocteau près des Romains

Peut-être y verras-tu Royère

Auquel je baise les deux mains

Car c’est un cœur et c’est une âme

et c’est un poète en un mot

Sur son beau front brille une flamme

Dans sa main fleurit un rameau

Mais moi pour l’Hellespont antique

Ne suis pas parti cette fois

Il fait un soleil électrique

Voici venir le plus doux des mois »

It is always moving, even when the text is known, to discover its first handwritten version. This is the case for this poem, part of an epistolary correspondence between Apollinaire and his friend André Billy (1882-1971) during the great war, in March 1915, unveiled after more than a hundred years. We immediately note the absence of punctuation, dear to the poet.

Billy, in March 1915, had remained in Paris, where he was annoyed, while Wilhelm de Kostrowitzky following his voluntary enlistment was training in Nîmes in the artillery and used abundantly the stationery of the Tortoni café where he had his habits. André Billy was a journalist and in August 1915 he was going to publish in the Mercure de France part of their “Correspondance poétique”, taking care, however, not to write the names in clear. The number in blue in the margin of the manuscript is probably intended for The Mercure. André Billy had commented on this publication almost on the spot: “Young writers, torn by the war from their favorite occupations, have adopted a charming use: they correspond in verse, which proves at least, we will agree, a morale of all rest. /We have before us a number of these poetic epistles. Let us hope that someone, later, will bring them all together.

They are valuable literary and psychological documents. ». This means that these poems written quickly without a doubt were however more or less clearly intended for publication. The authors were aware of the testimonial value of these poems and took care of their texts. As early as 1923, André Billy published this correspondence in his Living Apollinaire, with his own poems that shed light on Apollinaire’s allusions: their mutual friends, the Cevennes Léo Larguier, who was wounded in September 1915 and later sat like Billy at the Académie Goncourt, the young Cocteau, Jules Romains. : names that will become famous in the twentieth century. This poem imbued with nostalgia and melancholy is far from showing the slightest enthusiasm for war.

If we look more closely, it does not lack irony. Billy, waiting for an assignment in the administration, barracked in a school, complains by bantering about his inaction in Paris, furnished by the game of “roulette” that one has some trouble imagining. Apollinaire opposes his wish to see him join the Cocteau, the Romains, that is to say all those who for one reason or another are not in the trenches. Cocteau later enlisted to be finally reformed for health reasons; Jules Romains did not go to war. As for Jean Royère, born in 1871, he could not be mobilized. His presence in the enumeration is curious, we can suspect Apollinaire of having yielded to the constraint of the rhyme in “era”…. while paying tribute to a writer he admired. He was about to be sent to the Dardanelles, which did not happen. Between these two true friends, the humor of the first, which “adds” on his fate, perhaps to hide his embarrassment to be in the company of the “ambushes” as the irony of the second remain on a pleasant mode. On April 26, Apollinaire wrote to Billy: « Je te le dis, André Billy, que cette guerre/C’est Obus-Roi/Beaucoup plus tragique qu’Ubu mais qui n’est guère/Billy crois-moi/Moins burlesque, ô mon vieux, crois-moi c’est très comique ». The fun is gone…

This correspondence testifies, among other things, to the need for soldiers far from their intellectual and emotional background to keep in touch to endure the separation. If Apollinaire in March 1915 had not yet known the front, he already knew that death was lurking.

References:

André Billy, Apollinaire vivant, Éditions de la Sirène, 1923.

Victor Martin-Schmets, Correspondance générale tome 2, 1915

Lettres reçues par Guillaume Apollinaire, tome 1, A-C

Apollinaire – Œuvres poétiques, bibl. de la Pléiade, p. 770