MONTIJO (de), Impératrice Eugénie (1826-1920)

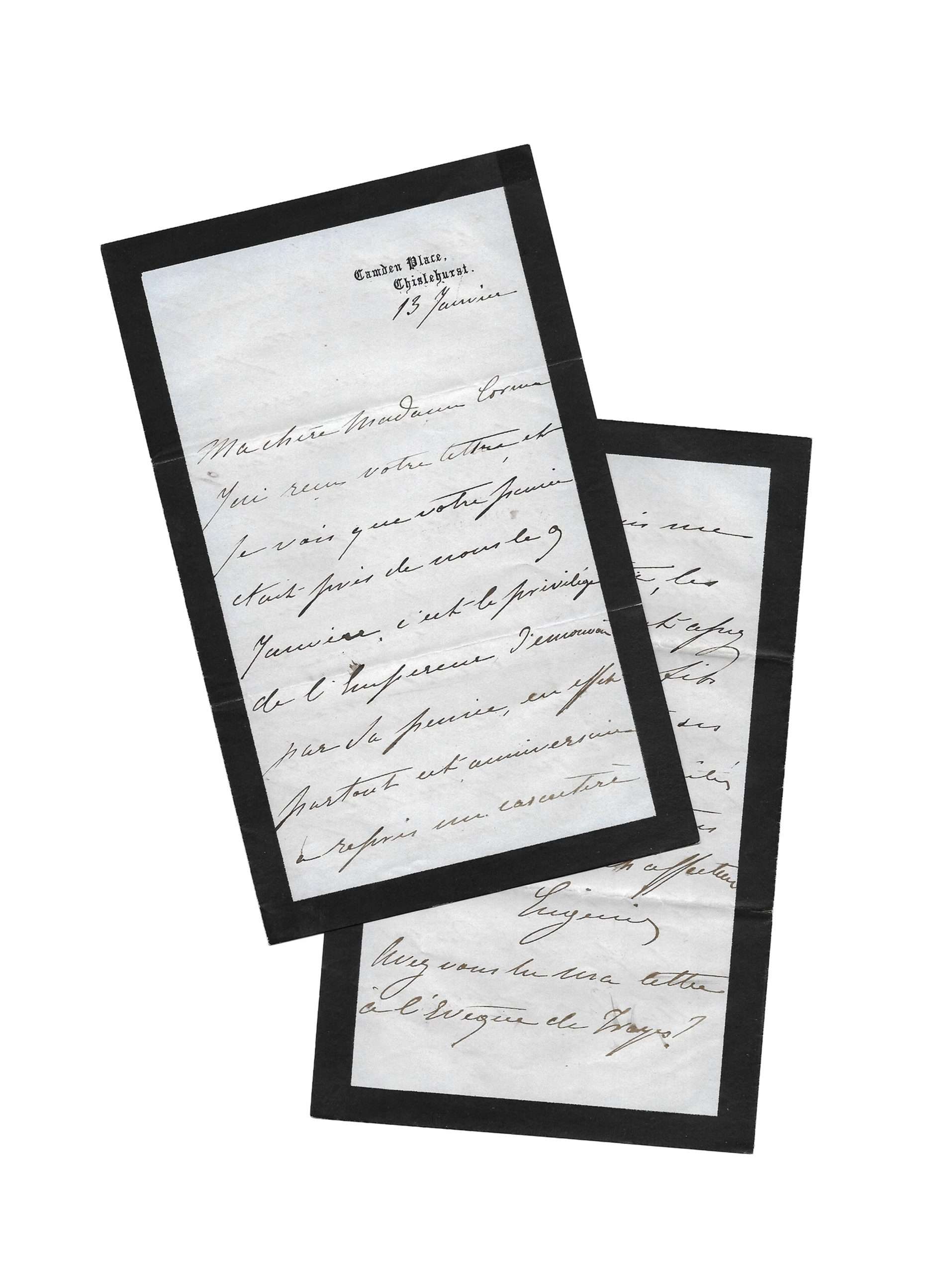

Autograph letter signed « Eugénie » to Hortense Cornu

[Camden Place, Chislehurst] 13th January [1875], 8 pp. in-8°, mourning paper

« What a singular destiny which makes it so that the most French hearts, the Napoleons, must all to this day be laid in a foreign coffin »

Fact sheet

MONTIJO (de), Impératrice Eugénie (1826-1920)

Autograph letter signed « Eugénie » to Hortense Cornu

[Camden Place, Chislehurst] 13th January [1875], 8 pp. in-8°, mourning paper

Tiny ink stains, usual fold marks, otherwise excellent condition throughout

Long and important letter from the Empress, written four days after the second anniversary of the death of Napoleon III

She painfully evokes the exhumation of the Emperor’s remains to be placed in the red granite sarcophagus of Aberdeen, a gift from Queen Victoria

« Ma chère Madame Cornu,

J’ai reçu votre lettre et je vois que votre pensée était près de nous le 9 janvier [date anniversaire de la mort de l’empereur]. C’est le privilège de l’empereur d’émouvoir par sa pensée ; en effet partout cet anniversaire a repris un caractère d’actualité et chacun pensait qu’il devait plus qu’un souvenir à cette grande mémoire. Nous avons eu, ici, une cérémonie bien touchante, il a été porté dans le sarcophage que la Reine [Victoria] a fait faire pour lui ; j’ai assisté cachée à tous, et je puis vous assurer qu’en le voyant enlever il me semblait qu’on m’arrachait le cœur ; est-ce sa dernière demeure ? Je ne puis le croire, mais il me semble que je ne pourrai jamais rentrer sans lui ! Quand j’étais en France je me souviens d’avoir dit l’Empereur, ‘je ne me sens étrangère que le jour des morts, tout ce que j’aime, grâce à Dieu vit, et ce jour où chacun va retrouver les morts je m’aperçois que je n’ai rien sous terre’. Aujourd’hui, au contraire, si je devais rentrer en France sans lui, je serais étrangère toujours !… Quelle singulière destinée qui fait que les cœurs les plus français, les Napoléons, doivent tous jusqu’à présent être déposés dans un cercueil étranger, deux anglais ! et un autrichien !

Je ne puis hélas vous parler d’autre chose aujourd’hui. Mon fils [le Prince Impérial] continue à travailler. Dieu veuille qu’on lui laisse finir ses études, je ne crains rien tant que les agitations stériles ; tout semble préparer son avenir ! Mais quelle tâche difficile il a devant lui ! Quand le peuple comprendra-t-il la différence qu’il y a entre ceux qui l’aiment et ceux qui l’exploitent ! Mon pauvre et cher Empereur s’est usé à la peine, et jamais on ne devinera les secrètes douleurs de ce martyr de trois ans ! Seul, il proposait cette émanation divine, le pardon des injures, et Dieu seul sait à quelles dures épreuves il a été soumis. Ma santé est assez bonne mais je ne puis me décider à sortir, les journées passent assez vite. Mon fils vous envoie tous ses souvenirs d’amitié et croyez-bien à tous mes sentiments affectueux.

Eugénie

Avez-vous lu ma lettre à l’Évêque de Troyes ? »

The sincere friendship between Queen Victoria and the imperial couple began in 1855 during the alliance between Great Britain and France against Russia during the Crimean War. This friendship withstood the passage of time and the vicissitudes of French foreign policy, which led the imperial couple to find exile in England after the fall of the Second Empire in September 1870. In a final tribute to the late emperor, Victoria had his remains transferred to a red granite sarcophagus in Aberdeen, where he rests to this day. On reading this letter, Eugenie apparently could not hold back her emotion, “hidden [from] everyone”.

At the end of the letter, Eugenie mentions her son the Prince Imperial who, in January 1875, left Woolwich School with the rank of officer in the British army. Three years later, to combat the monotony of exile and to demonstrate his military skills, he enlisted, despite his mother’s resistance, in the ranks of the English army. He went to southern Africa to suppress a revolt by the Zulus, before succumbing to an ambush under their arrows on 1 June 1879.

Goddaughter of Queen Hortsense and foster-sister of Napoleon III, Hortense Cornu (1809-1875), the addressee of this letter, was one of the strong personalities of the imperial entourage. She was the daughter of a chambermaid of Hortense de Beauharnais, mother of the future emperor. Brought up close to him, she retained a great influence for a long time by encouraging him towards politics. She brought him books to Ham Prison and took notes for his study work. Erudite, with a taste for archaeology, she herself published works of history and literature, and held a popular salon. A republican, she distanced herself from Louis-Napoleon after the coup d’état of December 1851, and opened a salon of her own to the enemies of the Empire. She drew nearer, however, to the Emperor after the Italian campaign, and was again admitted into her familiarity in 1862. Born Hortense Lacroix, she had married the painter Sébastien Cornu in 1834. She died in embarrassment at Longpont-sur-Orge on 16 May 1875.

Provenance:

Jean-Claude Lachnitt’s estate