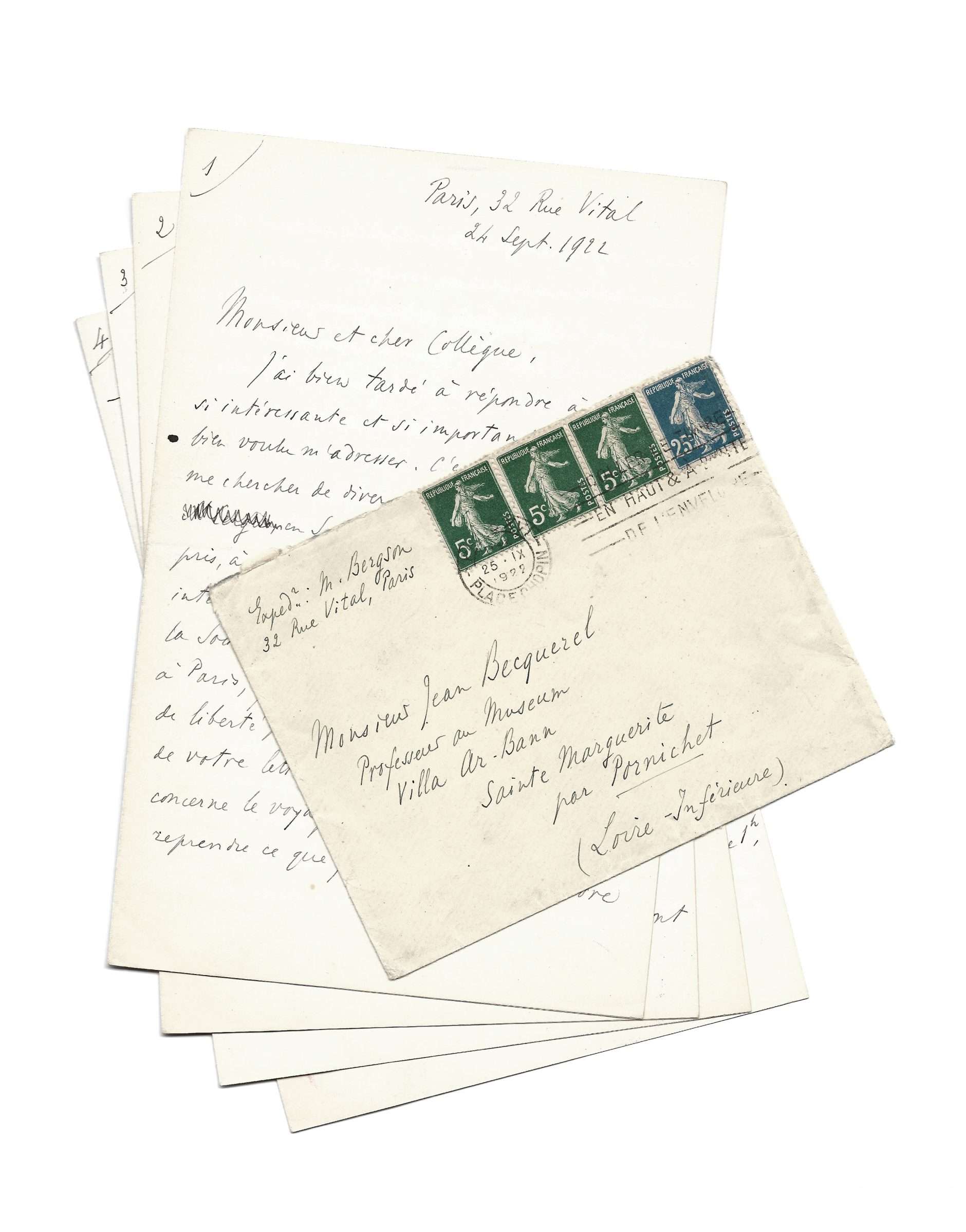

[EINSTEIN] BERGSON, Henri (1859-1941)

Autograph letter signed « Henri Bergson » to Jean Becquerel

Paris, 24 Sept[ember] 1922, 16 pages in-8°

« From the point of view of the theory of Relativity, there is no longer absolute motion or absolute immobility »

Fact sheet

[EINSTEIN] BERGSON, Henri (1859-1941)

Autograph letter signed « Henri Bergson » to Jean Becquerel

Paris, 24 Sept[ember] 1922, 16 pages in-8° with envelope

Some typographic pencil notes

A highly significant letter, partly unpublished, on the issues and interpretation of the theory of relativity – This intervention of the philosopher continues up to this day to create multiple controversies

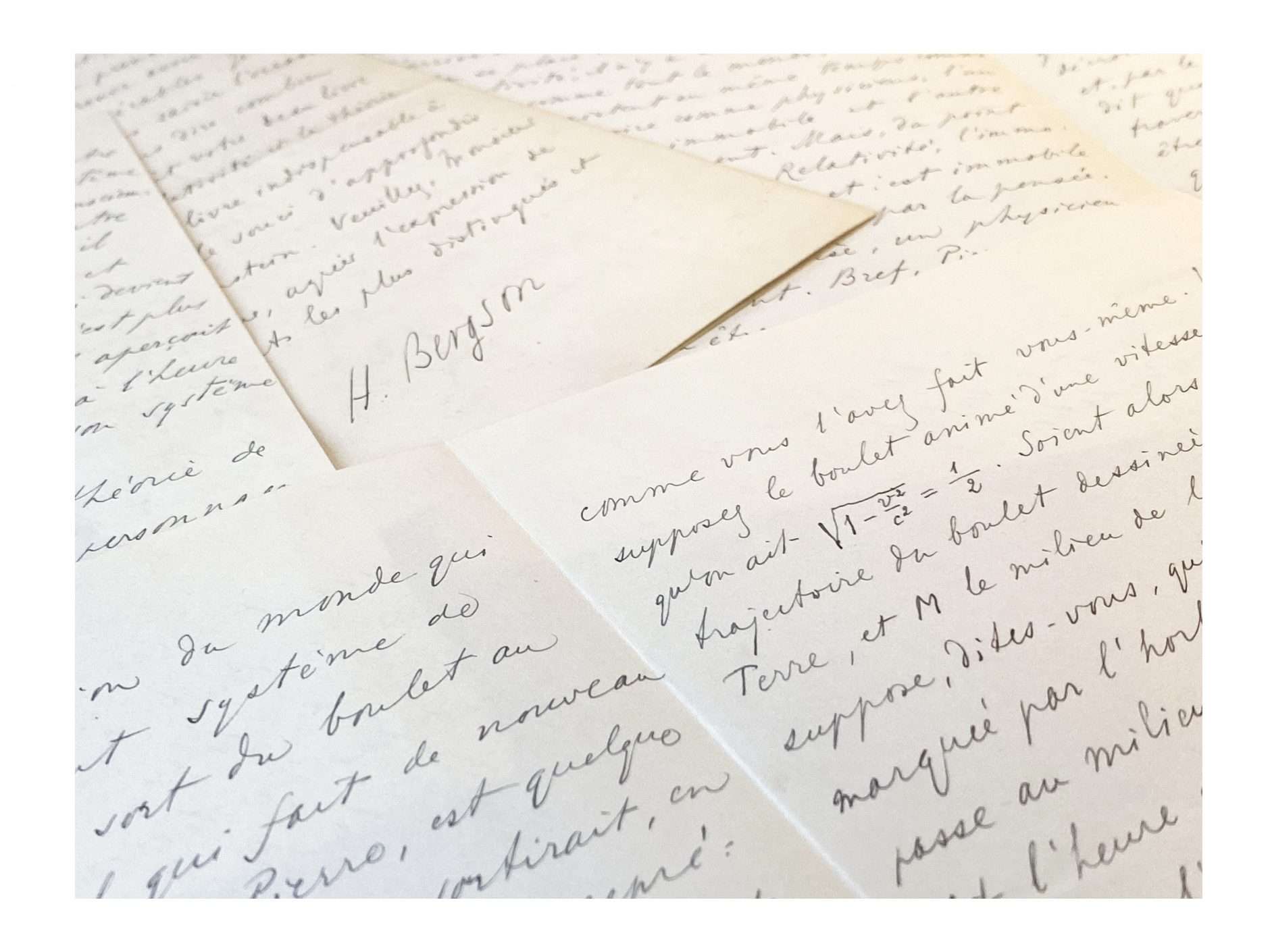

We transcribe here only a few fragments of this letter which, although known in its substance, has remained unpublished to this day

« Monsieur et cher collègue,

J’ai bien tardé à répondre à la lettre, si intéressante et si importante, que vous avez bien voulu m’adresser. C’est qu’elle est allée me chercher de divers côtés, et m’a atteint en Suisse, à un moment où j’étais pris, à Genève, par le travail de « Coopération intellectuelle » qui nous avait été confié par la Société des nations. Me voici de retour à Paris ; je profite de mes premiers instants de liberté pour vous écrire. Le passage essentiel de votre lettre est naturellement celui qui concerne le voyage en boulet. Laissez-moi reprendre ce que j’ai dit dans mon livre [Durée et simultanéité, paru à l’été 1922] en y joignant quelques explications complémentaires.

Il y a d’abord deux remarques importantes à faire.

1° Si l’on se place en dehors de la Théorie de la Relativité, on conçoit un mouvement absolu et, par là même, une immobilité absolue ; il y aura dans l’univers des systèmes réellement immobiles. Mais, si l’on pose que tout mouvement est relatif, que devient l’immobilité ? Ce sera l’état du système de référence, je veux dire du système où le physicien se suppose placé, à l’intérieur duquel il se voit prenant des mesures et auquel il rapporte tous les points de l’univers. […]

2° Si l’on se place en dehors de la Théorie de la Relativité, on conçoit très bien un personnage Pierre absolument immobile au point A, à côté d’un canon absolument immobile ; on conçoit aussi un personnage Paul, intérieur à un boulet qui est lancé loin de Pierre, se mouvant en ligne droite d’un mouvement uniforme absolu vers le point B et revenant ensuite, en ligne droite et d’un mouvement uniforme absolu encore, au point A. Mais du point de vue de la Théorie de la Relativité, il n’y a plus de mouvement absolu ni d’immobilité absolue […] Paul une fois lancé dans l’espace n’est plus qu’une représentation de l’esprit, une image — ce que j’ai appelé un « fantôme » ou encore une « marionnette vide ». C’est ce Paul en route (ni vivant ni conscient, n’existant plus que comme image) qui est dans un Temps plus lent que celui de Pierre. […] Le Paul qui sort du boulet au retour du voyage, le Paul qui fait de nouveau partie alors du système de Pierre, est quelque chose comme un personnage qui sortirait, en chair et en os, de la toile où il était représenté en peinture : c’était à la peinture et non pas au personnage, c’était à Paul référé et non pas à Paul référant, que s’appliquaient les raisonnements et les calculs de Pierre pendant que Paul était en voyage. […] Je ne voudrais pas clore sans saisir l’occasion qui s’offre à moi de vous dire combien m’a intéressé et instruit votre beau livre sur « Le principe de relativité » et la « Théorie de la gravitation » , – livre indispensable à tous ceux qui ont le souci d’approfondir la théorie d’Einstein. Veuillez, Monsieur et cher collègue, agréer l’expression de mes sentiments les plus distingués et dévoués

H. Bergson »

In publishing Durée et simultanéité (published by Alcan in the summer of 1922), Bergson was taking a risk that he probably did not measure himself. The purpose of this essay was to discuss the philosophical issues of the theory of relativity. The criticism of his scientific colleagues was not long in coming. Those of Einstein in the first place, deploring the “blunders” or “dumplings” of the philosopher. In France, it was Jean Becquerel who opened fire with a letter addressed directly to the author, and of which this document constitutes the reply.

At the time, Becquerel held a chair of applied physics at the Museum of Natural History. He wrote a textbook entitled Le Principe de relativité et la théorie de la gravitation (Gauthier-Villars, 1922), which made him one of the first introducers of Einsteinian theory in the French context. Two sources give an idea of the content of Becrerel’s letter: his article published the following year (“Critique de l’ouvrage durée et Simultaneity de M. Bergson”, Bulletin scientifique des étudiants de Paris, 10 (2), March-April 1923), and the extract given by Bergson himself in the first of three appendices added to the 1923 edition of Durée et simultanéité – appendix which also contains, with a few lines, the entirety of his answer. Bergson then chose to preserve the anonymity of his correspondent in order to avoid giving the impression of a “polemic” (according to the interview of December 30, 1923 with Jacques Chevalier). He merely evokes “a letter, very interesting, which was addressed to us by a most distinguished physicist.”

The discussion crystallizes on a specific point: the interpretation of the slowdown of moving clocks predicted by the theory. The famous “twin paradox” attributed to Paul Langevin provides a pictorial version of the problem, as part of a Jules Verne-style narrative: an astronaut (here “Paul”), embarked on a “ball journey”, would find himself, on his return, younger than his twin brother who remained on Earth (here, “Pierre”), as if time had passed less quickly for him! In his letter, Becquerel insists on the fact that the theory of relativity speaks of time actually measured on both sides by observers in relative motion. Bergson repeats, by clarifying it, the argument developed in his book, namely that the differences relate less to real times than to fictitious times, that is to say, times attributed to other observers who acquire at the same time the status of simple images, or “ghosts”. Thus the “dilation” of durations associated with the slowing down of moving clocks is only a “perspective effect”. Bergson is led to this conclusion by a strict interpretation of the principle of relativity: between two observers in relative motion, there is a “perfect symmetry”, each can consider itself motionless or mobile with respect to the other. Multiple empirical confirmations have since objectively proved the philosopher wrong, but the question of the status of time in relativity, as well as that of the relevance of the arguments exchanged, continues to fuel contemporary philosophical debates. In that sense, that letter constitutes a key part of the case.

Bibliography:

Correspondances II, éd. Florent Serina & Caterina Zanfi, Puf, 2024, p. 369-370 (partial transcription only)

We thank Mr. Elie During for the information he kindly communicated to us