RIMBAUD, Arthur (1854-1891)

Autograph letter signed « Rimbaud » to his family

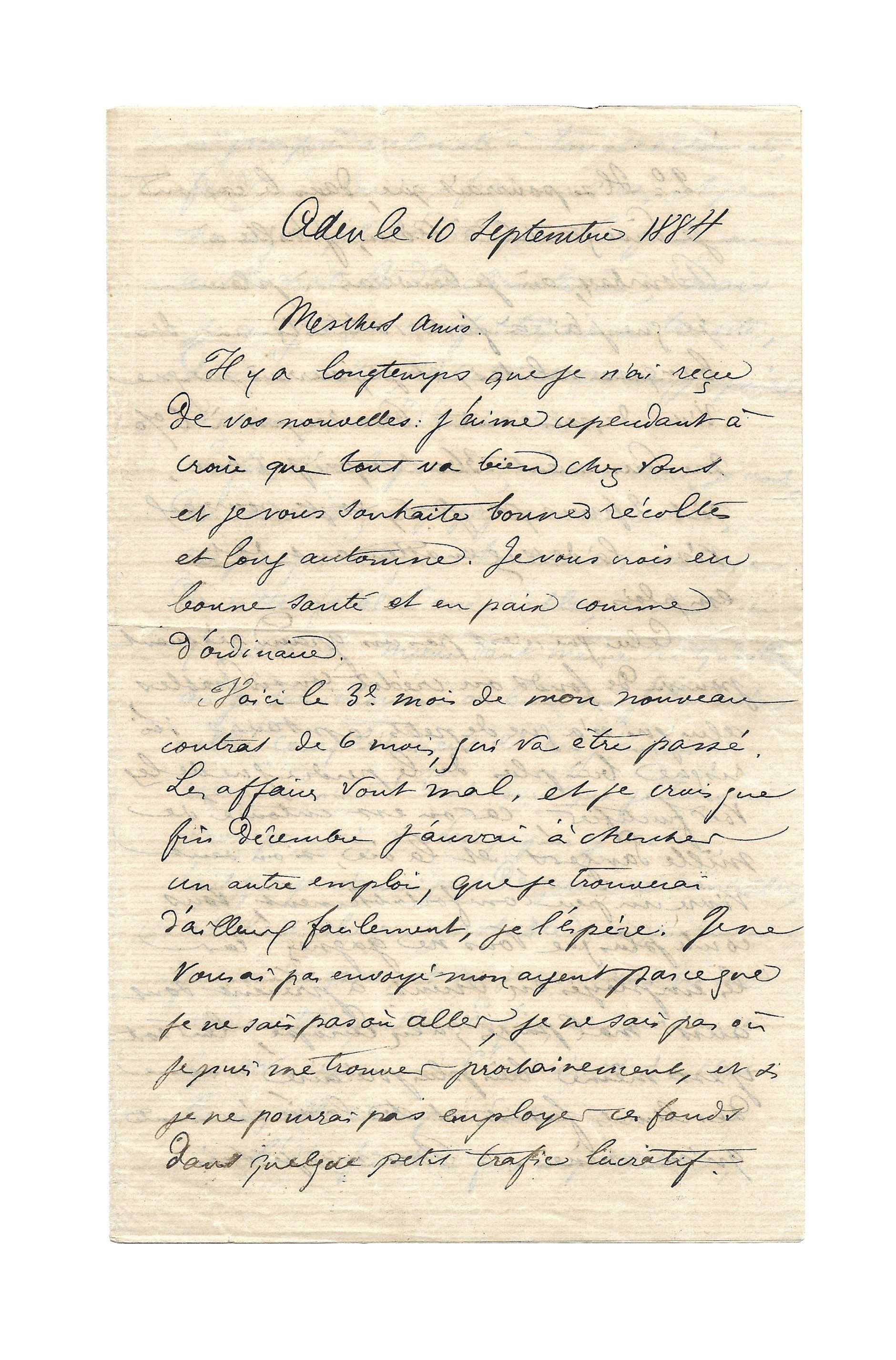

Aden, 10th September 1884, 4 pp. in-8° on laid paper

« And since every man is a slave in this miserable fatality »

Fact sheet

RIMBAUD, Arthur (1854-1891)

Autograph letter signed « Rimbaud » to his family

Aden, 10th September 1884, 4 pp. in-8° on laid paper

Supplied with bespoke leather maroquin sleeve

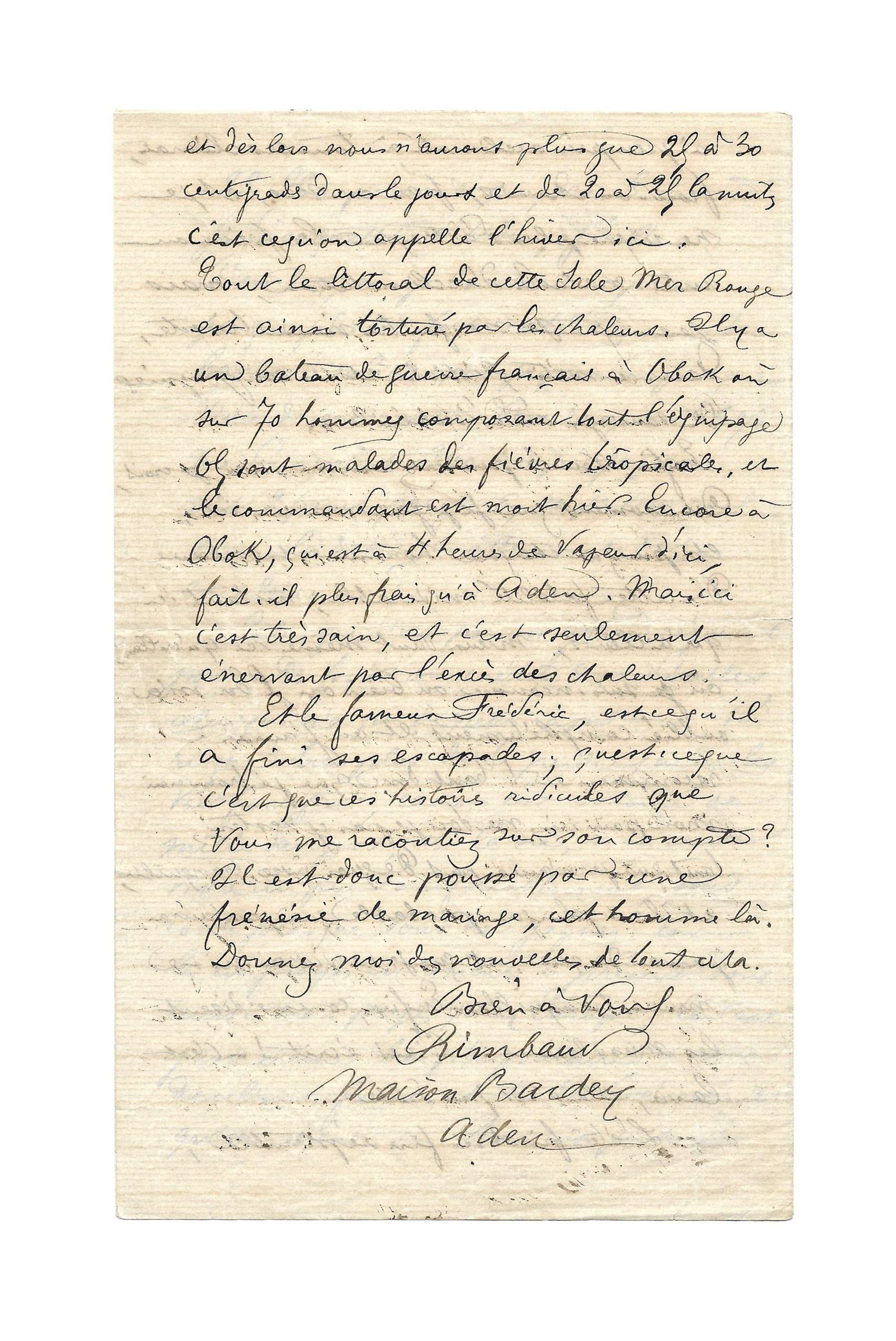

From the former collections of Louis Barthou and Baroness Alexandrine de Rothschild, from the Bernard Loliée sale

Imbued with fatalism, Arthur Rimbaud speaks of his difficult existence in Aden

One of his most significant travel letters still in private hands

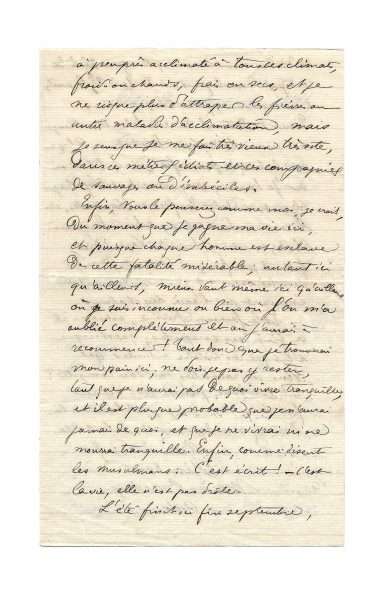

« Mes chers amis,

Il y a longtemps que je n’ai reçu de vos nouvelles : j’aime cependant à croire que tout va bien chez vous et je vous souhaite bonnes récoltes et long automne. Je vous crois en bonne santé et en paix comme d’ordinaire.

Voici le troisième mois de mon nouveau contrat de six mois, qui va être passé. Les affaires vont mal, et je crois que fin décembre j’aurai à chercher un autre emploi, que je trouverai d’ailleurs facilement, je l’espère. Je ne vous ai pas envoyé mon argent parce que je ne sais pas où aller, je ne sais pas où je puis me trouver prochainement, et si je ne pourrai pas employer ces fonds dans quelque petit trafic lucratif.

2° Il se pourrait que, dans le cas où je doive quitter à Aden, j’aille à Bombay, où je trouverai à placer ce que j’ai à fort intérêt sur des banques solides, et je pourrai presque vivre de mes rentes : 6.000 roupies à 6% me donnerait 360 roupies par an, soit 2 francs par jour, et je pourrais vivre là-dessus en attendant des emplois.

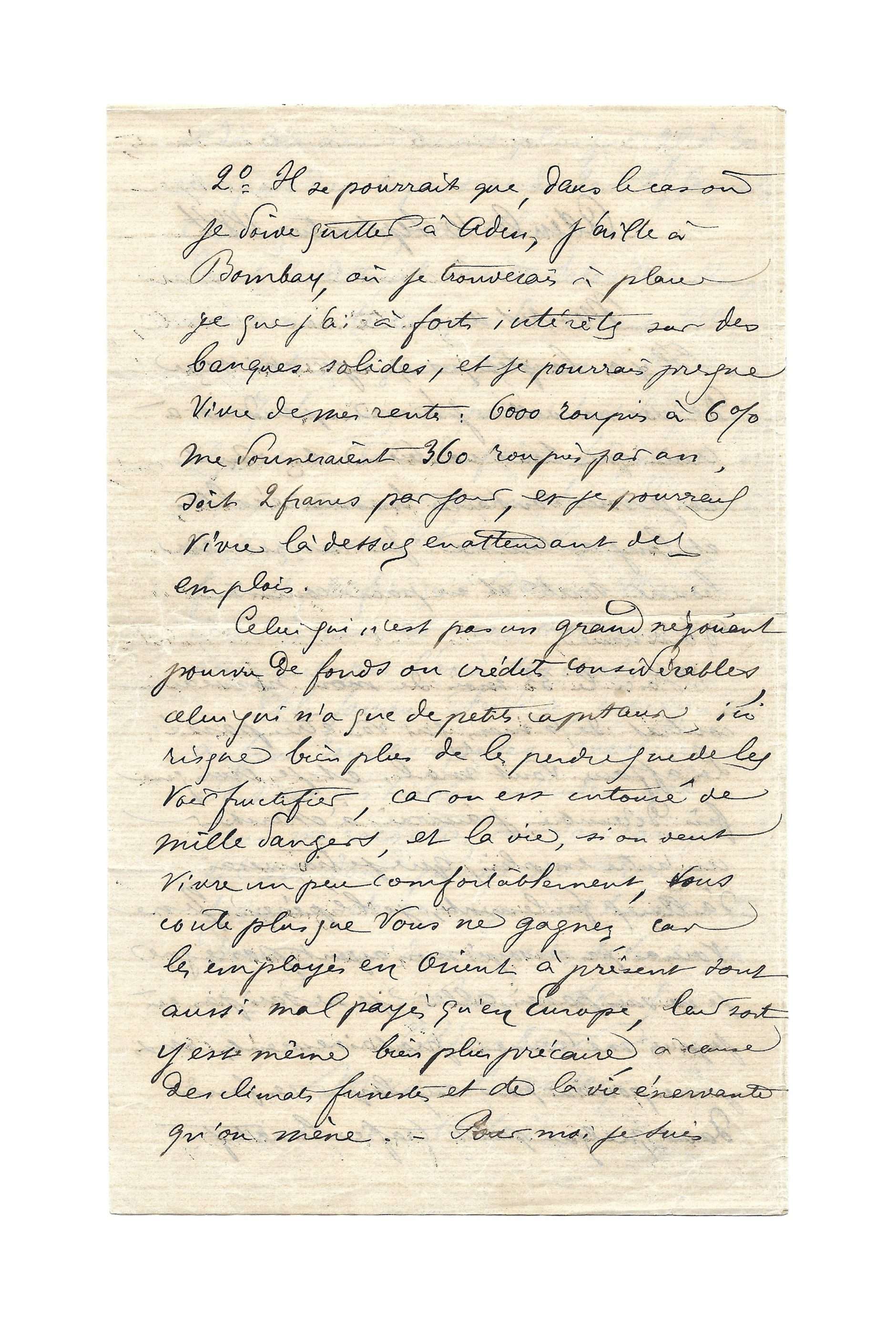

Celui qui n’est pas un grand négociant pourvu de fonds ou crédits considérables, celui qui n’a que de petits capitaux, ici risque bien plus de les perdre que de les voir fructifier, car on est entouré de mille dangers, et la vie, si on veut vivre un peu confortablement, vous coûte plus que si vous ne gagnez, car les employés en Orient à présent son aussi mal payés qu’en Europe, leur sort u est même bien plus précaire, à cause des climats funestes et la vie énervante qu’on mène. – Pour moi je suis à peu près acclimaté à tous ces climats, froids ou chauds, frais ou secs, et je ne risque plus d’attraper les fièvres ou autres maladies d’acclimatation, mais je sens que je me fais très vieux très vite, dans ces métiers idiots et ces compagnies de sauvages ou d’imbéciles.

Enfin, vous le penserez comme moi, je crois, du moment que je gagne ma vie ici, et puisque chaque homme est esclave en cette fatalité misérable, autant ici qu’ailleurs où je suis inconnu ou bien où l’on m’a oublié complètement et où j’aurai à recommencer ! Tant donc que je trouverai mon pain ici, ne dois-je pas y rester, tant que je n’aurai pas de quoi vivre tranquille et il est plus que probable que je n’aurai jamais de quoi, et que je ne vivrai ni ne mourrai tranquille. Enfin, comme disent les musulmans : C’est écrit ! – C’est la vie, elle n’est pas drôle.

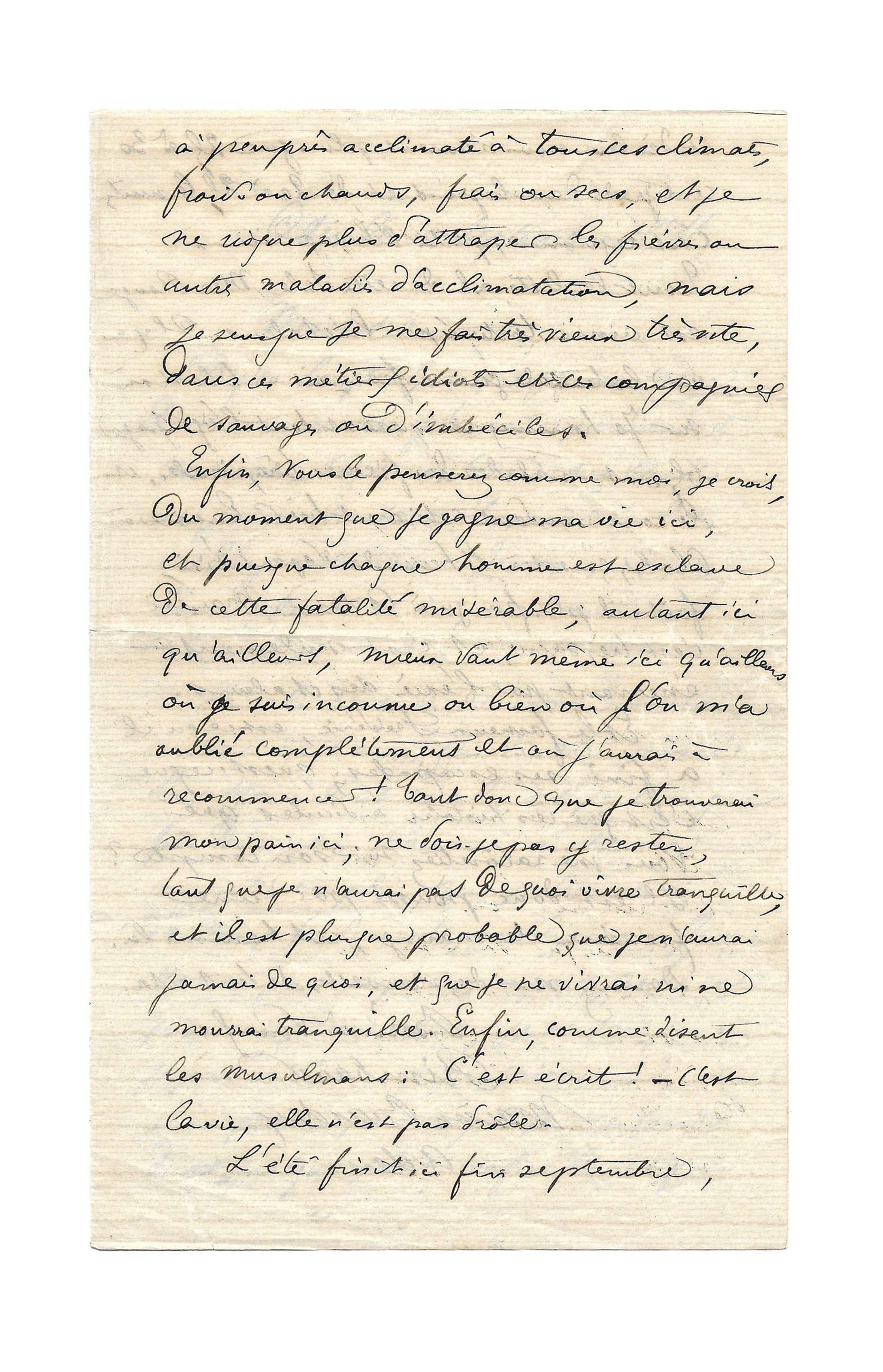

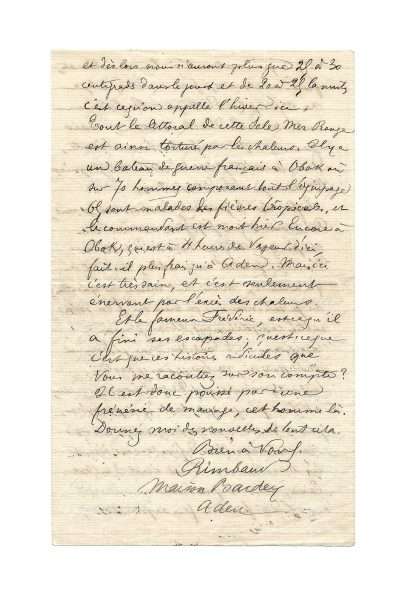

L’été finit ici fin septembre, et dès lors nous n’aurons plus que 25 à 30 centigrades dans le jour et de 20 à 25 la nuit, c’est ce qu’on appelle l’hivers ici. Tout le littoral de cette sale mer Rouge est ainsi torturé par les chaleurs. Il y a un bateau de guerre français à Obok où sur 70 hommes composant tout l’équipage 65 sont malades des fièvres tropicales, et le commandant est mort hier. Encore à Obok, qui est à quatre heures de vapeurs d’ici, fait-il plus frais qu’à Aden. Mais ici c’est très sain, et c’est seulement énervant par l’excès des chaleurs.

Et le fameux Frédéric, est-ce qu’il a fini ses escapades ; qu’est-ce que c’est que ces histoires ridicules que vous me racontiez sur son compte ? Il est donc poussé par une frénésie de mariage, cet homme-là. Donnez-moi des nouvelles de tout cela.

Bien à vous,

Rimbaud.

Maison Bardey, Aden. »

At the beginning of March, Rimbaud left Harar, abyssinia: the city where he worked had become “uninhabitable, because of the troubles of the war” (letter to his family, April 24, 1884). After six weeks of “desert travel” (same letter), he arrived in Aden, Yemen, around April 20. The Bardey house, which employed him, experienced serious financial difficulties and closed its two counters, in Harar and Aden. For a few months, he lived on his savings: if we believe what he wrote to his family on May 5, he set aside “twelve or thirteen thousand francs”. The horizon clears in the second half of May. His employer, Alfred Bardey, has gone to Marseille to seek funds and activities will resume. In mid-June, Rimbaud and Bardey signed a new contract, which committed them for six months, from 1 July to 31 December 1884.

The heat is unbearable in Aden during the summer months. Europeans who are not used to it get sick. Rimbaud resists. He has kept his temperament and the expatriate his sense of acclimatization. Yet homesickness is here. He eagerly awaits the letters that have come to him from France and the mail seems to him desperately slow between the continents. In the letter he sent to his family on September 10, 1884, he inquired about the “harvests” at the end of summer: as every year, his mother, Vitalie, and his sister, Isabelle, carried out seasonal transhumance, to come to work in the fields, passing from their residence in Charleville to their property in Roche, about forty kilometers away.

But what makes this letter highly exceptional is the feeling it expresses, of integral fatalism. As if he had to draw conclusions from everything he tells his family, from everything he suffers in the lands where he came in the hope of earning a living, Rimbaud, as if away from the practical, commercial, climatic questions that he develops in the letter, says what he understands about life, the meaning of life: “Every man is a slave to this miserable fate” from which, there or elsewhere, he cannot escape. This sense of fatality, and of “miserable fatality”, formulated here, far from Europe, was already formulated in this great programmatic text, or premonitory: A Season in Hell. And as radical as the rupture was and as real as the distance of someone who wanted to flee from all feelings, and all philosophical heritage, the idea of the man “slave” of fatality returns to him like the eye of Cain, whose presence he verified, “as much here as elsewhere”.

“I hate misery,” wrote Rimbaud, in the “Farewell” of A Season in Hell. He imagined then that he could free himself from Christian law, from the curse of his baptism. Life, misery and fate have caught up with him, to the point that he only has to quote the creed of another religion, that of “muslims”: “It is written”. He remained the Godless man he was in his late teens, except when it comes to hearing what religions say about universal misery and the tragic fate of every human creature.

Since there is only “life”, and it is “not pleasant”, as much to live “here as elsewhere”, writes Rimbaud, before adding: “better even here than elsewhere”. But does he really think so? The attention he pays to his family, to everything he has left and whose remoteness, following a well-known existential paradox, brings him closer together, suggests another feeling. We know this terrible logic of nostalgia, which the Romantics celebrated and which is only a way of experiencing dissatisfaction: the fir tree, in the snows, dreams of the sun of the East and palm of Egypt of northern chills. This is the meaning of Rimbaud’s life, which this letter and the purpose it makes, trivializing human misery, reveal.

Hence the attention he pays to his family, to the activities of his mother and sister, to whom he has become accustomed to addressing himself by calling them, in the masculine; “dear friends”, as if the circle to which his letters are intended should naturally widen. An attention that is focused on the work of the fields, the harvests, and on the erratic behaviors of his brother, Frédéric, his eldest of a little less than a year: Frédéric was born on November 3, 1853, Arthur on October 20, 1854.

At the end of the letter – in cauda venenum – Rimbaud speaks without amenity of his brother, “the famous Frédéric”, as he calls him with contemptuous irony: “famous”, in the sense that the youngest knows what to stick to on the elder, in the sense also that Frédéric’s reputation encumbers him: “it would bother me enough, for example, if anyone knew that I have such a fool as a brother”, he wrote in another letter to his family on 7 October of the same year.

Frédéric is desperate to get married. Rimbaud himself, when he imagines a happy future, thinks of marriage. But Frédéric makes a fool of himself. He struggles to the point of appearing “possessed by a frenzy of marriage.” It is necessary to imagine above all that he exercises this frenzy in the depths of the Ardennes society, which triggers the maternal fury: Vitalie will oppose with all her strength the marriage of his eldest son, to the point of referring to justice. Rimbaud may not share such social prejudices, at least in their provincial and bourgeois sense, but he has other reasons to despise his brother, whom he considers an inferior being, ontologically.

And he took his mother and sister as a witness to this atavism: “he is a perfect idiot, we have always known it, and we always admired the hardness of his caboche” (letter of October 7, 1884). It is necessary to weigh the weight of this “we” and this “always”, to imagine the power of a contempt that has its origins in childhood, as it is necessary to oppose this way of repudiating an elder brother, unworthy of replacing the absent father, to the image shown to us in the photograph taken in Charleville in 1866, where the two brothers appear as first communicants, in the deceptive resemblance of their young age, opening their big eyes to the horizon of life, a life that would install between them the impassable abyss of incommunicability. David Le Guillou gave the full measure of this incommunicability in a beautiful romanticized essay on “the other Rimbaud”, as he calls Arthur’s brother (L’Autre Rimbaud, Paris, L’Iconoclaste, 2020).

It is understandable that Isabelle, by communicating in 1896 the text of Rimbaud’s letters to her future husband, Paterne Berrichon, did not dispense with the last paragraph of this letter, whose published text was therefore incomplete for a long time. The disagreement with Frédéric was no doubt consummated, but she was reluctant to spread such family secrets, at a time when, after Arthur’s death, Frédéric and his descendants were called to bear the name Rimbaud.

Provenance:

Famille Rimbaud

Paterne Berrichon (Letter sold directly by him to Louis Barthou)

Collection Louis Barthou, 15-17 juin 1936, catalogue IV, n°2117

Collection [Alexandrine de Rothschild], vente anonyme, Drouot, 29 mai 1968

Collection Bernard Loliée

Bibliography:

Rimbaud, Œuvres complètes, éd. A. Guyaux, Pléiade, p. 551-552

Arthur Rimbaud – Correspondance, éd. J-J. Lefrère, Fayard, 2007, p. 400-401