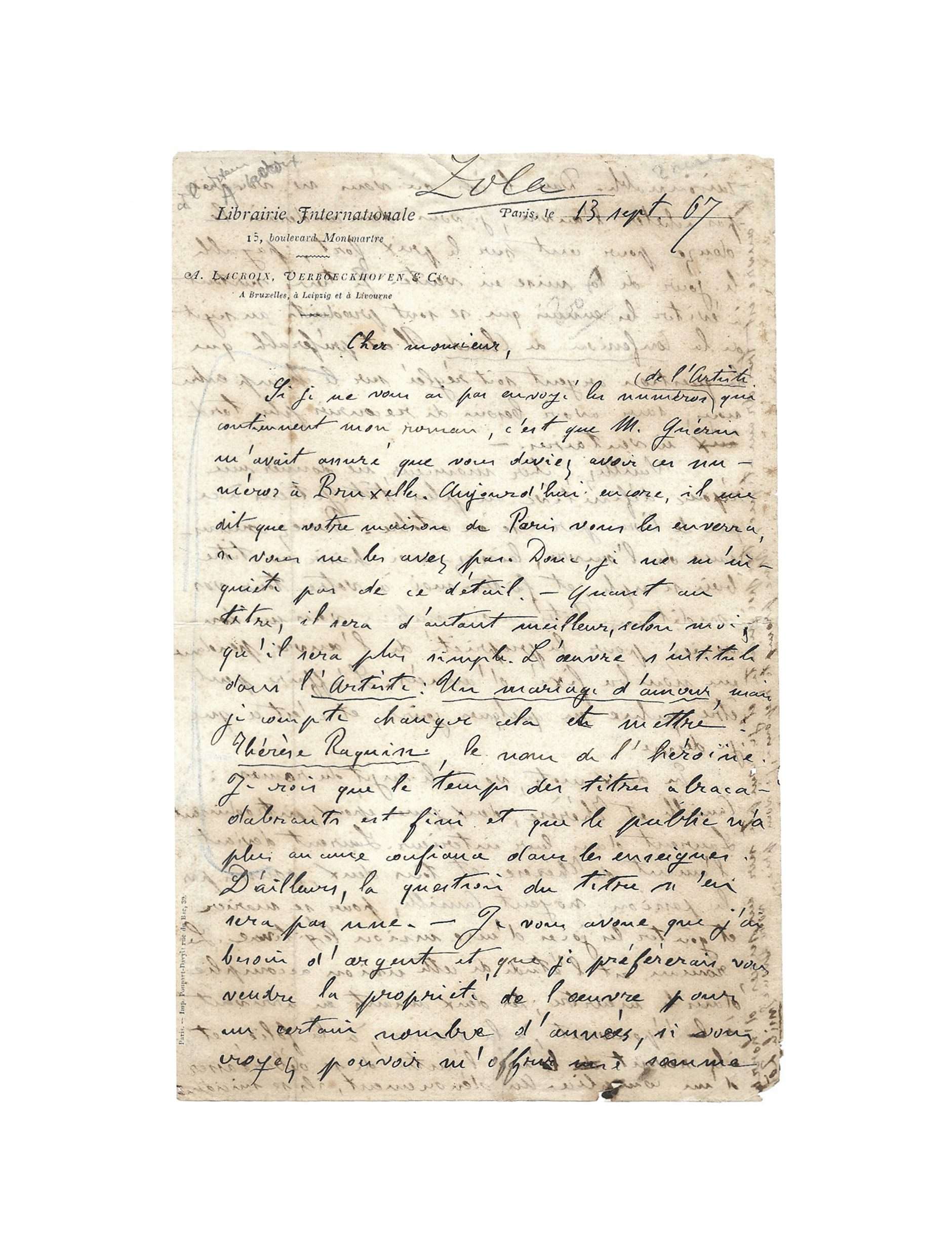

ZOLA, Émile (1840-1902)

Autograph letter signed « Emile Zola » [to Albert Lacroix]

Paris, 13 Sept[ember] 1867, 2 pp. in-8°

« I’m counting on a horror success »

Fact sheet

ZOLA, Émile (1840-1902)

Autograph letter signed « Emile Zola » [to Albert Lacroix]

Paris, 13 Sept[ember] 1867, 2 pp. in-8° in black ink, letterhead of the Librairie Internationale

« Zola » annotation (from period and in black ink) from another hand, small gaps in the lower margin affecting a letter, slits in the folds, discreet repairs with Japan paper

A remarkable letter from the very young Zola, a few weeks before the launch of Thérèse Raquin, the first novel that made him famous to the general public – Expressing a pressing financial need, the writer nevertheless cherishes high ambitions for the success of his work

It is in this very same letter that Zola first announces the final title of the book

« Cher Monsieur,

Si je ne vous ai pas envoyé les numéros de L’Artiste¹ qui contiennent mon roman, c’est que M. Guérin [employé de la Librairie Internationale] m’avait assuré que vous deviez avoir ces numéros à Bruxelles. Aujourd’hui encore, il me dit que votre maison de Paris vous les enverra, si vous ne les avez pas. Donc je ne m’inquiète pas de ce détail. Quant au titre, il sera d’autant meilleur, selon moi, qu’il sera plus simple. L’œuvre s’intitule dans L’Artiste : Un Mariage d’amour, mais je compte changer cela et mettre : Thérèse Raquin, le nom de l’héroïne. Je crois que le temps des titres abracadabrants est fini et que le public n’a plus aucune confiance dans les enseignes. D’ailleurs, la question du titre n’en sera pas une. Je vous avoue que j’ai besoin d’argent et que je préférerai vous vendre la propriété de l’œuvre pour un certain nombre d’années, si vous croyez pouvoir m’offrir une somme raisonnable. Dans le cas où vous ne voudriez pas acheter l’œuvre, je vous demanderais le douze pour cent sur le prix fort, payable le jour de la mise en vente. Je tiens surtout à éviter les ennuis qui se sont produits au sujet de La Confession de Claude [son deuxième ouvrage, publié également chez Lacroix deux ans auparavant]. Il est préférable que la question argent soit réglée sur-le-champ entre nous, sans avoir besoin de recourir plus tard à des inventaires.

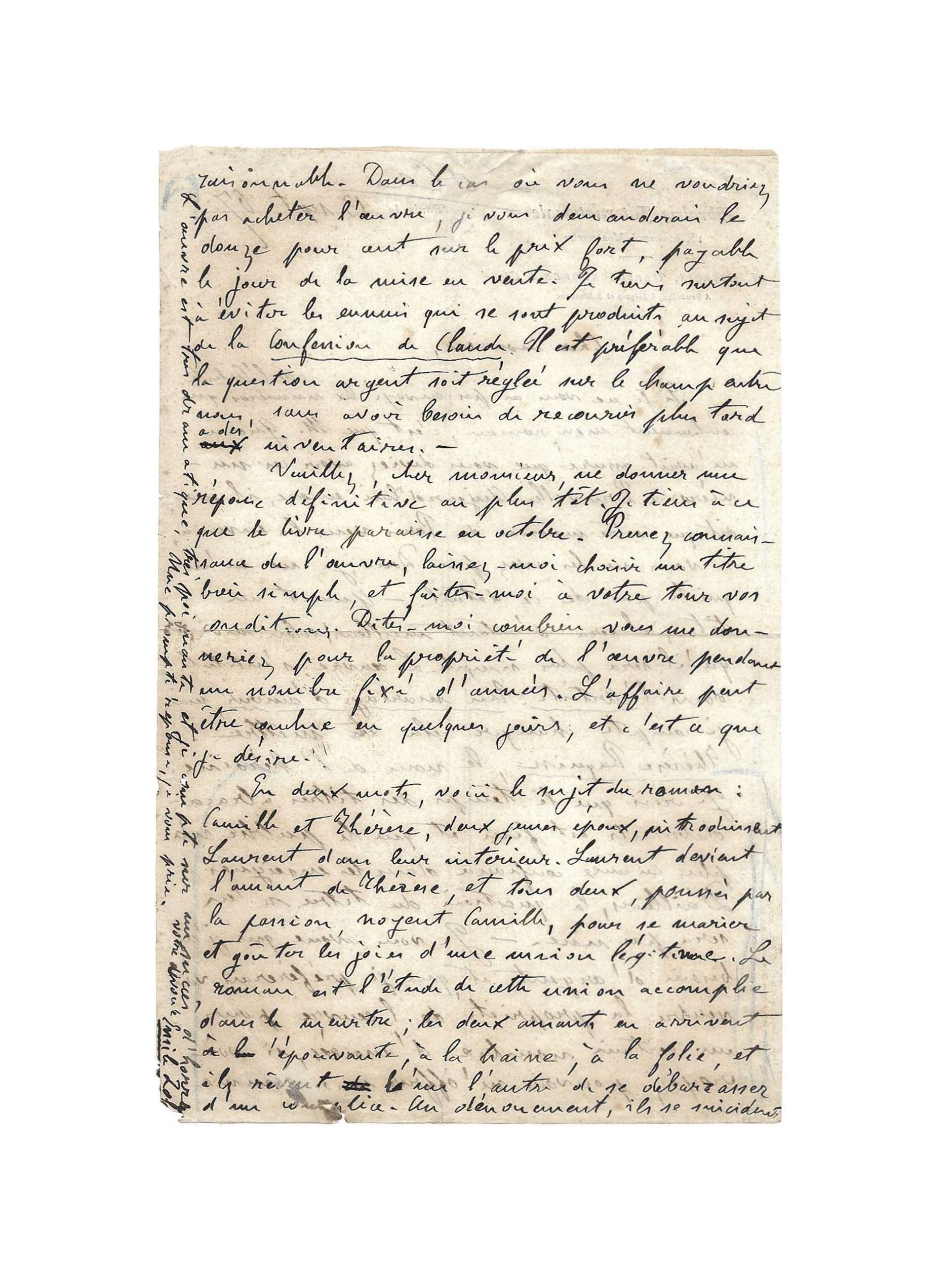

Veuillez, chez Monsieur, me donner une réponse définitive au plus tôt. Je tiens à ce que ce livre paraisse en octobre. Prenez connaissance de l’œuvre, laissez-moi choisir un titre bien simple², et faites-moi à votre tour vos conditions. Dites-moi combien vous me donneriez pour la propriété de l’œuvre pendant un nombre fixé d’années. L’affaire peut être conclue en quelques jours, et c’est ce que je désire.

En deux mots, voici le sujet du roman : Camille et Thérèse, deux jeunes époux, introduisent Laurent dans leur intérieur. Laurent devient l’amant de Thérèse, et tous deux, poussés par la passion, noient Camille, pour se marier et goûter les joies d’une union légitime. Le roman est l’étude de cette union accomplie dans le meurtre ; les deux amants en arrivent à l’épouvante, à la haine, à la folie, et ils rêvent l’un et l’autre de se débarrasser d’un complice. Au dénouement, ils se suicident. L’œuvre est très dramatique, très poignante, et je compte sur un succès d’horreur.

Une prompte réponse, je vous prie.

Votre dévoué

Émile Zola »

1- Illustrated weekly magazine (from 1831 to 1904), renowned for having published prints and quality writers. The novel, originally titled Un Mariage d’amour, had previously been serialized in the magazine.

2- On November 9, 1867, A. Lacroix and Verboeckhoven, booksellers-publishers, informed Zola that they had given the proof to print the title and cover of Thérèse Raquin, adding: “We have suppressed the word study which was, in our opinion, of the worst effect on the cover and which, on the other hand, could have harmed the volume, in the sense that it might make people believe that your volume was an arid and too serious work, and thereby alienate a whole class of readers. In any case, this subtitle seemed useless to us; Isn’t that your opinion too? »

The young Zola, then 27 years old, already gives us a glimpse of the confidence that would later be known for, that of a writer who was quite certain of his work. He nevertheless remained in need, which he explains here to Lacroix, the latter being known among other things for having been the first publisher of Les Misérables.

« I think the time for crazy headlines is over… »

What is implied by Zola’s choice to call the book Thérèse Raquin tends to erase the stage of serialization in L’Artiste. The writer flatters the publisher and therefore defines the “second birth” of the novel. This sense of the title, which Zola was already refining at this time, would later become one of his great talents, giving decisive importance to this significant beginning.

« The work is very dramatic, very poignant, and I’m counting on a horror success »

By summarizing the story at the end of the letter, Zola shows us that he is always very scrupulous in adapting to the recipient’s preferences. He insists on the plot, the dramatic scope, the psychological dimension, and finally the stylistic innovations. He makes hypotyposis his trademark at key moments. At that time, Zola was the only standard-bearer of naturalism, a literary movement that succeeded realism, which he had exposed three years earlier in his famous missive to Anthony Valabrègue by means of the famous metaphor of the “trois écrans”. Zola’s reading effects are therefore data that can be easily converted into terms of editorial success.

Thérèse Raquin was severely judged by the critics, notably by Louis Ulbach, who published in Le Figaro a violent article entitled “La littérature putrid”. However, it was a success and Zola became known to the general public. His career as a novelist was definitively launched…

Bibliography:

Correspondance, t. I, éd. du CNRS, Les Presses de l’université de Montréal, p. 522-523, n°199